Gun Violence, Stigma, and Mental Illness: Clinical Implications

Gun Violence, Stigma, and Mental Illness: Clinical Implications

March 25, 2015 | Special Reports, Trauma And Violence

Linked Articles

New legislation in a number of states requires mental health professionals to assess their patients for the potential to commit gun crimes. For instance, New York state law mandates that mental health professionals report anyone who “is likely to engage in conduct that would result in serious harm to self or others” to the state’s Division of Criminal Justice Services, which then alerts local authorities to revoke the person’s firearms license and confiscate his or her weapons. Similarly, a recently passed bill in Tennessee requires mental health professionals to report “threatening patients” to local law enforcement.

Supporters of these types of laws argue that they provide important tools for law enforcement officials to identify potentially violent persons—and understandably so.

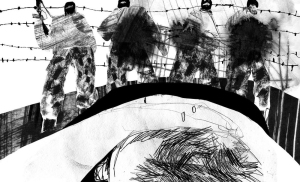

US policymakers and the general public look to psychiatry, psychology, neuroscience, and related disciplines as sources of certainty in the face of the often incomprehensible terror and loss that gun violence inevitably produces.

And to be sure, persons with mental illness who have shown violent tendencies should not have access to weapons that could be used to harm themselves or others.

shutterstock.com

shutterstock.com

However, the notion that psychiatric attention might prevent gun crime is more complicated than it might seem. New research undertaken by me and my colleague, Professor Ken MacLeish, warns of the potential pitfalls of such laws if they are unaccompanied by other community-based or antistigma interventions.1 We systematically reviewed the key psychiatry, psychol- ogy, public health, and sociology literature that addressed connections between mental illness and gun violence between 1960 and 2014. We also used our own primary source historical research on violence and mental illness, and American gun culture.2-4

Our review critically addresses 4 central assumptions that underlie many US political and popular associations between gun violence and mental illness:

• That mental illness causes gun violence

• That psychiatric diagnosis can predict gun crime before it happens

• That US mass shootings teach us to fear mentally ill loners

• That because of the complex psychiatric histories of mass shooters, gun control “won’t prevent” another Tucson, Aurora, Newtown, or Navy Yard

Each of these statements is certainly true in particular instances. At the same time, our research shows how these seemingly self-evident assumptions are replete with complicated and at times contradictory assumptions. At the aggregate level, the notion that mental illness causes gun violence stereotypes a diverse population of persons with psychiatric conditions and oversimplifies links between violence and mental illness. Moreover, notions of mental illness that emerge in relation to gun violence frequently reflect larger cultural issues that become obscured when mass shootings come to stand for all gun crime and when “mentally ill” ceases to be a medical designation and becomes a sign of violent threat.

Our research also shows how anxieties about insanity and gun violence are imbued with often unspoken anxieties about race, politics, and the unequal distribution of violence in American society. In the current American landscape, these tensions play out most clearly in differing cultural responses to, for instance, high-profile shootings in places like Newtown (where headlines located pathology in the perpetrator’s brain) and New York City (where news commentators wondered whether murderous actions were motivated by “black politics.”5)

Our analysis suggests that similar, if less overt, tensions suffuse discourses linking guns and mental illness more broadly, in ways that subtly connect “insane” gun crimes with often unspoken assumptions about “white” individualism or “black” communal aggression.

Ultimately, our research challenges psychiatry to think deeply about potentially untenable situations in which mental health practitioners become the persons most empowered to make decisions about gun ownership—and most liable for failures to predict gun violence—if these situations are not accompanied by larger reforms that address the social, structural, and indeed psychological implications of gun violence in the US.

Reblogged this on HumansinShadow.wordpress.com.

LikeLike

March 6, 2016 at 3:13 pm